Roger Shattuck, The Banquet Years (4) -- From the Salons to the Café

Of all the stages that made up the city, the most formalized and demanding was the salon. The aristocracy still cultivated the

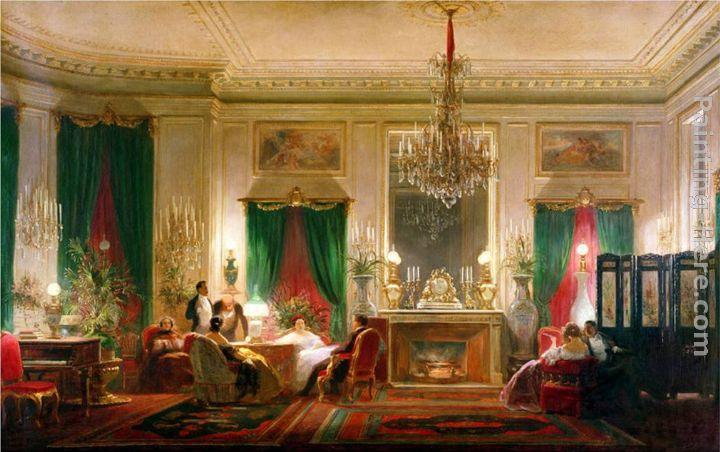

Charles Giraud, Salon of Princess Mathilde Bonaparte |

conversation of what were assumed to be great minds. The revolution had not destroyed the old aristocracy, but had set up beside it another: the Napoleonic. The most elevated member of the new nobility, Princesse Mathilde Bonaparte, Napoleon's niece, did not mince her words: "The French revolution? Why, without it I'd be selling oranges in the streets of Ajaccio." Her sympathy and loyalty had begun by attracting Théophile Gautier, Flaubert, and Renan to a dangerously liberal salon during the Second Empire. During the Third Republic she again began receiving in her house in the Rue de Berri (today the Belgian Embassy) and continued until after 1900, when she was over eighty. Dumas fils, Henri de Régnier, Maupassant, and Anatole France came to her simple early dinners, which Proust described affectionately in one of his best Figaro society articles.

In barely a generation, Princesse Mathilde had learned an aristocratic ease which gave her the proper "presence" for a salon. Her guests never felt like performing animals. Madame Aubernon, however, a somewhat vulgar aristocrat of the old school, passionately interested in literature and the theater, conducted her rival salon like a lion tamer. About a dozen guests attended her poorly cooked dinners in the Rue d'Astorg, and Madame Aubernon alone decided the subject for discussion. One guest at a time was permitted to orate, and his chances of a second invitation depended on the brilliance of his performance. The hostess silenced any disorderly interruption by ringing a little porcelain bell which stood at her right hand. One evening when Renan was discoursing at some length, she had several times to call to order the dramatist Labiche (author of The Italian Straw Hat). When she finally asked him to speak, he admitted with some reluctance that he had only wanted to ask for more peas. On another occasion Madame Aubernon asked D'Annunzio point-blank what he thought of love; his reply was not designed to bring him a second invitation: "Read my books, Madame, and let me eat my dinner." A lady, asked with similar abruptness to speak her piece on the subject of adultery, replied, "You must pardon me, Madame. For this evening I prepared incest."

In barely a generation, Princesse Mathilde had learned an aristocratic ease which gave her the proper "presence" for a salon. Her guests never felt like performing animals. Madame Aubernon, however, a somewhat vulgar aristocrat of the old school, passionately interested in literature and the theater, conducted her rival salon like a lion tamer. About a dozen guests attended her poorly cooked dinners in the Rue d'Astorg, and Madame Aubernon alone decided the subject for discussion. One guest at a time was permitted to orate, and his chances of a second invitation depended on the brilliance of his performance. The hostess silenced any disorderly interruption by ringing a little porcelain bell which stood at her right hand. One evening when Renan was discoursing at some length, she had several times to call to order the dramatist Labiche (author of The Italian Straw Hat). When she finally asked him to speak, he admitted with some reluctance that he had only wanted to ask for more peas. On another occasion Madame Aubernon asked D'Annunzio point-blank what he thought of love; his reply was not designed to bring him a second invitation: "Read my books, Madame, and let me eat my dinner." A lady, asked with similar abruptness to speak her piece on the subject of adultery, replied, "You must pardon me, Madame. For this evening I prepared incest."

As the salon declined for lack of ladies trained to conduct one and through disappearance of the basic attitude of hommage on which the institution rested, the need for a verbal arena increased. One of the principal changes of la belle époque was that the great performers moved from the salon into the café. Here anyone could enter, and each man paid for his drink. As far back as the mid-eighteenth century artists and writers in Paris had begun to rely increasingly on the stimulus and exchange of the café. (They were served by young boys, whence comes the word garçon for waiter.) The term boulevardier was now invented to describe men whose principal accomplishment consisted in appearing at the proper moment in the proper café. More than the  salon, the café came to provide a free marketplace of ideas and helped France produce its steady succession of artistic schools. The Napolitain, the Weber, the Vachette--the famous cafés of the period following 1885--were sprinkled from the fashionable boulevards to the Latin Quarter to the slopes of Montmartre. The Café Guerbois and the Nouvelle Athènes in the sixties and seventies had nurtured the first artistic movement entirely organized in cafés: impressionism. By the end of the nineteenth century the café represented a ritual which could absorb the better part of the day. "In the old days," wrote Jean Moréas, one of the great habitués and lion of the Vachette, "I arrived around one in the afternoon . . . stayed till seven, and then went to dine. About eight we came back, and didn't finally leave until one in the morning." It was a life unto itself.

salon, the café came to provide a free marketplace of ideas and helped France produce its steady succession of artistic schools. The Napolitain, the Weber, the Vachette--the famous cafés of the period following 1885--were sprinkled from the fashionable boulevards to the Latin Quarter to the slopes of Montmartre. The Café Guerbois and the Nouvelle Athènes in the sixties and seventies had nurtured the first artistic movement entirely organized in cafés: impressionism. By the end of the nineteenth century the café represented a ritual which could absorb the better part of the day. "In the old days," wrote Jean Moréas, one of the great habitués and lion of the Vachette, "I arrived around one in the afternoon . . . stayed till seven, and then went to dine. About eight we came back, and didn't finally leave until one in the morning." It was a life unto itself.

Salon and café demanded performances on a small and intense scale from a group of highly trained actors. There was an equally specialized class of Parisians who played, however, to a larger audience. In the title of his famous play, first produced in 1885, Dumas fils brilliantly named this special world: Le demi-monde. The beautiful, cultured, kept women had undisputed sway over styles in women's dress. Fashion is the most unpredictable and competitive theater of all, and they brought it to a peak of perfection. Mesdemoiselles les cocottes (also more crudely known as les horizontales)were on display mornings in the Bois in their carriages, filled the tables at the Café de Paris and the Pré Catelan in the evening, and entertained lavishly

at night in their own tastefully decorated hôtels particuliers. One of the best known, Mademoiselle Jane Cambrai, practiced no deceit in exploiting her lover, a successful rag dealer. He was in no way suitable company--or host-at her brilliant parties, towhich Tout-Paris swarmed at the turn of the century. She saw to it that he remained happily upstairs playing bridge with a few of his own friends, and he showed no disgruntlement over the crowd below dancing and banqueting at his expense. These creatures of pleasure and fashion and canniness lived truly in a "half world" from which they might fade into penury and loneliness, or out of which they might emerge dramatically by marriage into nobility and respectability. A cocotte had not arrived in her profession until she had inspired at least one suicide, unsuccessful of course, and three or four duels, and had déniaisé (initiated) her lover's eldest son.